Federated Computing for the Masses

Understanding Fluid Flow

In March 2013 a joint team of researchers

from Rutgers Discovery Informatics Institute

and Computational Physics and Mechanics Laboratory

at Iowa State University launched a large scale computational

experiment to gather the most comprehensive to date information

on the effects of pillars on microfluid channel flow.

The experiment is unique as it demonstrates that a single user

operating entirely in a user-space can federate multiple, geographically distributed and heterogeneous

HPC resources, to obtain a platform with cloud-like

capabilities able to solve large scale computational engineering problems.

In this web page we provide details of the experiment, we show some of the results and summarize our findings.

News

- August 19, 2014 - Computing in Science & Engineering published our extended report on federated computing for the masses.

- November 17, 2013 - We presented our work on computational federations at the 6th Workshop on Many-Task Computing on Clouds, Grids, and Supercomputers (MTAGS) 2013.

- November 02, 2013 - XSEDE 2012-2013 Annual Highlights Book includes a brief description of our project.

- July 19, 2013 - We are featured on the main NSF News web page. And here is the NSF news.

- July 12, 2013 - Science 2.0 published a story about sculpting fluid flows, which includes our expriment. You can read more at http://www.science20.com/news_articles/sculpting_tailormade_fluid_flows_microfluidic_channels-116279.

- June 28, 2013 - The UberCloud Compendium with 25 case studies from Round 1 and Round 2 of the experiment has been published. The compendium features our work, and is available at http://tci.taborcommunications.com/l/21812/2013-06-25/7tbh.

- June 4, 2013 - The UberCloud HPC Experiment Round 2 Final Report featuring our work has been published. It is available for download at http://www.hpcexperiment.com/Round2Report.pdf.

- May 22, 2013 - Digital Manufacturing Report and HPC in the Cloud posted stories about our experiment. You can read them here and here.

- May 13, 2013 - We finally launched the official web page of the experiment!

Challenge

The ability to control fluid streams at microscale has significant applications in many domains,

including biological processing, guiding chemical reactions, and creating structured materials, to name

just a few.

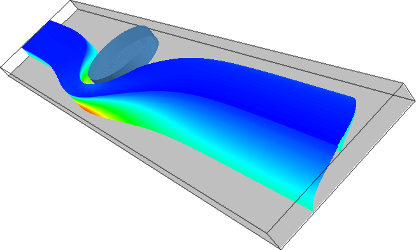

Recently, it has been discovered that placing pillars of different

dimensions, and at different offsets, allows "sculpting" the

fluid flow in microchannels. The design and placement of

sequences of pillars allows a phenomenal degree of flexibility

to program the flow. However, to achieve such a control it

is necessary to understand how the flow is affected by different

input parameters.

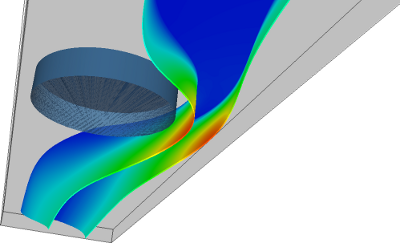

Using parallel, finite element and MPI-based Navier-Stokes equation solver,

we can simulate flows in a microchannel with an embedded pillar obstacle.

For a given combination of microchannel height, pillar location, pillar diameter,

and Reynolds number (4 variables), the solver captures qualitative and quantitative

characteristics of flow. However, to reveal how the

input parameters interplay, and how they impact flow, we have to

construct a phase diagram of possible flow behaviors.

Using parallel, finite element and MPI-based Navier-Stokes equation solver,

we can simulate flows in a microchannel with an embedded pillar obstacle.

For a given combination of microchannel height, pillar location, pillar diameter,

and Reynolds number (4 variables), the solver captures qualitative and quantitative

characteristics of flow. However, to reveal how the

input parameters interplay, and how they impact flow, we have to

construct a phase diagram of possible flow behaviors.

The problem is challenging for several reasons. The search space consists of

tens of thousands of points, and an individual simulation may take hundreds of

core-hours, even when executed on a state-of-the-art HPC cluster.

The individual simulations, although independent, are highly heterogeneous and

their cost is very difficult to estimate a priori, owing to varying

resolution and mesh density required for different configurations.

Finally, because the non-linear solver is iterative, it may fail to

converge for some combinations of input parameters, which necessitates

fault-tolerance.

Team

To solve the problem we formed a multidisciplinary team with joint expertise in high performance and distributed computing, and computational physics and mechanics:

- Javier Diaz-Montes, Rutgers Discovery Informatics Institute

- Baskar Ganapathysubramanian, Iowa State University

- Ivan Rodero, Rutgers Discovery Informatics Institute

- Manish Parashar, Rutgers Discovery Informatics Institute

- Yu Xie, Iowa State University

- Jaroslaw Zola, Rutgers Discovery Informatics Institute

Results

The goal of the experiment was to understand how different microchannel

parameters affect fluid flow. To achieve this we interrogated the 4D

parameter space formed by input variables (channel height, pillar

geometry, Reynolds number), in which a single point is equivalent to a

parallel Navier-Stokes simulation with a specific configuration. By discretizing

the search space we identified 12,400 simulations that would provide

sufficient data to construct phase diagrams. The total cost of these

simulations is approximately 1.5 million core-hours if run on the Stampede cluster

at TACC - one of the most powerful machines within XSEDE.

The massive size of this challenge makes it virtually impossible to execute on a single HPC resource (unless a special allocation

is provided). This is because of the associated computational cost, and more importantly, required throughput.

Therefore, we decided to depend on a user-centered computational federation. The idea is to

aggregate heterogeneous HPC resources in the spirit of how

volunteer computing assembles desktop computers. Specifically, we designed a federation model that:

- Is extremely easy to deploy and offers an intuitive API to meet expectations and needs of average user.

- Encapsulates cloud-like capabilities, e.g. on-demand resource provisioning, elasticity and resilience, to provide sustainable computational throughput.

- Provides strong fault-tolerance guarantees through constant monitoring of tasks and resources.

- Bridges multiple, highly heterogeneous resources, e.g. servers, clusters, supercomputers and clouds, to effectively exploit their intrinsic capabilities.

To achieve these goals we used

the CometCloud

platform. We combined the MPI-based solver with the CometCloud

infrastructure using the master/worker paradigm. In this scenario, the

simulation software serves as a computational engine, while CometCloud is

responsible for orchestrating the entire execution. The master component

takes care of generating tasks, collecting results, verifying that all

tasks executed properly, and keeping log of the execution. Here, each

task is described by a simulation configuration (specific values of the

input variables), and minimal hardware requirements. All tasks are

automatically placed in the CometCloud-managed distributed task space for

execution. In case of failed tasks the master recognizes the error and

either directly resubmits task (in case of a hardware error or a resource

leaving the federation), or regenerates it after first increasing the

minimal hardware requirements and/or modifying solver parameters (in case

of an application error and/or insufficient resources). Workers sole

responsibility is to execute tasks pulled from the task space. To achieve

this, each worker interacts with the respective queuing system and the

native MPI library via a set of dedicated drivers implemented as simple

shell scripts.

The resulting platform enabled us to execute the experiment in just two weeks. Below

are the main highlights of the experiment:

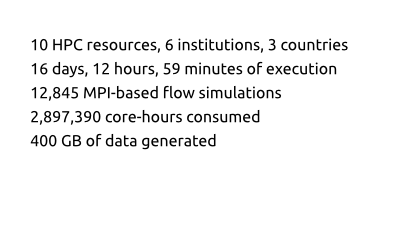

- 10 HPC resources, 6 institutions, 3 countries

- 16 days, 12 hours, 59 minutes of continuous execution

- 12,845 MPI-based flow simulations

- 2,897,390 core-hours consumed

- 400 GB of data generated

Distribution of HPC resources used in the experiment:

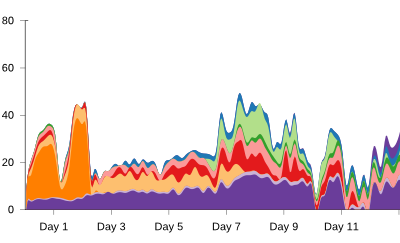

Summary of the execution:

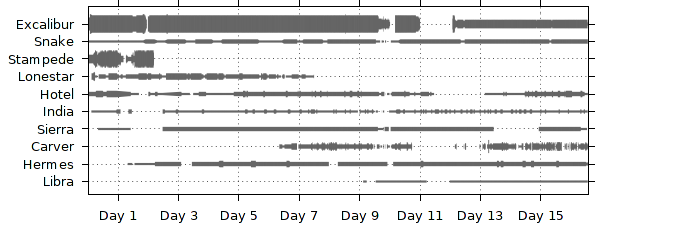

Utilization of different computational resources. Line thickness

is proportional to the number of tasks being executed at given point of time.

Gaps correspond to idle time, e.g. due to machine maintenance.

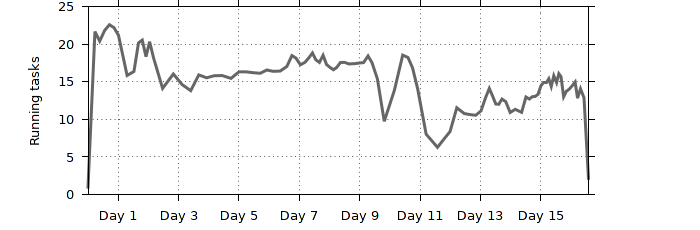

The total number of running tasks at given point of time.

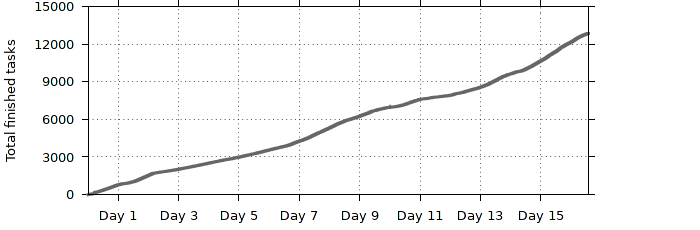

The total number of finished tasks at given point of time.

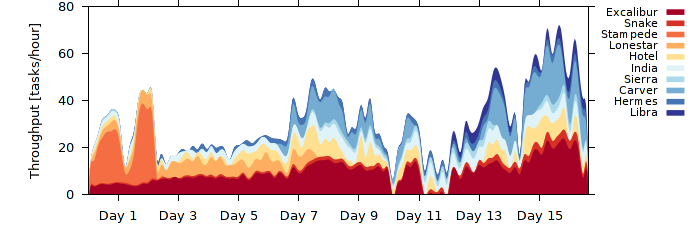

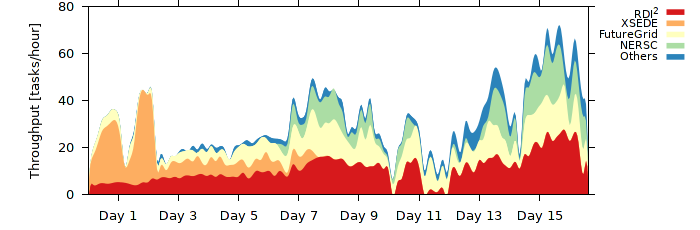

Dissection of throughput measured as the number of

tasks completed per hour. Different colors represent component throughput of different machines.

Thoughput contribution by different institutions.

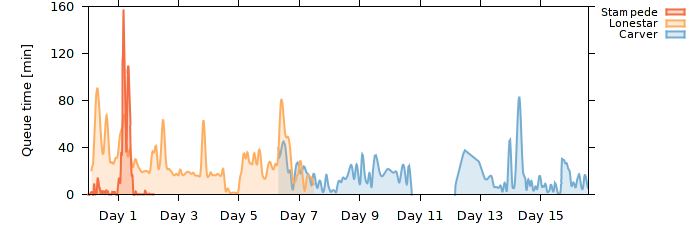

Queue waiting time on selected resources.

Resources

Below we provide several useful resources with additional information about the experiment:

If you would like to reference this work, please cite:

- J. Diaz-Montes, Y. Xie, I. Rodero, J. Zola, B. Ganapathysubramanian, M. Parashar, "Exploring the Use of Elastic Resource Federations for Enabling Large-Scale Scientific Workflows", In Proc. of Workshop on Many-Task Computing on Clouds, Grids, and Supercomputers (MTAGS), 2013.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported in part by the NSF under grants IIP-0758566, DMS-0835436, CBET-1307743, CBET-1306866, CAREER-1149365 and PHY-0941576. This project used resources provided by: XSEDE supported by NSF OCI-1053575, FutureGrid supported in part by NSF OCI-0910812, and NERSC Center supported by DOE DE-AC02-05CH11231. We would like to thank the SciCom group at the Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha, Spain (UCLM) for providing access to Hermes, and Distributed Computing research group at the Institute of High Performance Computing, Singapore (IHPC) for providing access to Libra. We wish to acknowledge the CINECA Italy, LRZ Germany, CESGA Spain, and the National Institute for Computational Sciences (NICS) for willing to share their computational resources. We would like to thank Dr. Olga Wodo for discussion and help with development of the simulation software, and Dr. Dino DiCarlo for discussions about the problem definition. We express gratitude to all administrators of systems used in this experiment, especially to Prentice Bisbal from Rutgers Discovery Informatics Institute and Koji Tanaka from FutureGrid, for their efforts to minimize downtime of computational resources, and a general support.

Copyright © 2014-2016 UB Scalable Computing Research Group

Copyright © 2013-2014 Rutgers Discovery Informatics Institute